Spirits distillation has a long and illustrious history, beginning with the the ancient Greeks, who ascribed sacred powers to the flammable and intoxicating liquids that resulted from early experiments in distilling wine. Dionysian cults incorporated these early spirits into religious rituals.

The earliest recorded wine distilling recipe is traced by some scholars to Anaxilaus of Thessaly, who was expelled from Rome in 28 B.C. for practicing magic.

There is sea-foam (salt) that has been heated in an earthenware wine-jar with new wine. When this has been boiled, if you apply a burning lamp to it, seizing the fire it sets itself alight, and if poured upon the head it does not burn at all.

“Boiled” was the Greek term for distilling, and salt was a common ingredient in medieval distilling recipes, for it raises the boiling point of wine by a few degrees.

Philosopher-chemists in Alexandria, Egypt practiced distilling from around the 2nd century B.C. They employed three or four different still types by the 1st century A.D, including one with three bronze outlet tubes invented by Maria the Jewess, a leading figure among their cohort. Their goal was not to distill spirits, but to obtain substances such as sulphur, mercury, and arsenic in order to alter the external composition of base metals and color them gold. This was part of a ritual practice, “a healing and release for all pain from the soul.” (Phusika kai mustika, 200 B.C.) In the process of bringing forth “fire” from base metal, it was thought, the alchemist’s soul would in turn become increasingly “fiery,” or closer to heaven.

Distilling itself is based on the concept that different substances turn to vapor at different temperatures. This was known to the Greeks for centuries before the sophisticated stills of the Egyptian philosopher-chemists. For example, ancient Greek sailors evaporated drinkable water from sea-water. They also learned that if wine was boiled in an open container, the fiery alcohol vapor escaped first. How to capture this elusive substance? The Greeks learned that if wine was heated slowly in a vessel with a small mouth covered by a bowl, alcohol would collect as condensed vapor inside the bowl, much as a pot lid collects droplets of condensed steam. The addition of a downward-slanted tube to the apparatus facilitated the cooling and condensation of the vapor and its collection in a handy receiving vessel. Thus our word “distill” comes from the Latin verb “destillare,” meaning “to drip down.”

At this time, distilling was not practiced for drinking enjoyment, but as part of the mystery religions of the era. Dionysus, the god of wine, was a revered deity who was honored with elaborate ceremonies at Delphi and other northern Greek cities from the 5th c. B.C. Poems describe how the maenads, female followers of Dionysus, would carry bronze stillheads during biennial rituals. Spirits were also flamed over the heads of initiates in rituals demonstrating the presence of the god. (When sulphur was added to the spirit, its theatrical flaming properties were increased, leaving hair and clothing safe and unmarked.) This practice was later taken over by the Gnostic Christian cults, who practiced a similar baptism by fire. In addition, the fact that spirits could preserve human flesh seemed to confirm for them the notion that they could confer long life or immortality when drunk. Interestingly, a 3rd century Coptic text may indicate that a botanical mixture including juniper, saffron, and cinnamon was infused into a distillate, which would make it the first known gin.

The Persians practiced distilling at the medical school in Jundishapur in the 6th century, where it was used to make herbal tinctures. The Arabs used large, elaborate stills to make rosewater and other herbal compounds, and to conduct innovative alchemical experiments in the 9th and 10th centuries, creating solvents for base metals and also attempting to discover an “elixir of life.” They apparently succeeded in distilling spirits, for the poet Abu Nuwas described a wine that “has the color of rainwater but is as hot inside the ribs as a burning firebrand.”

Cathar missionaries from the Balkan region brought the Anaxilaus recipe for wine distilling with them to Western Europe in the 12th century, as well as the practice of baptism by fire. The church eventually overcame its opposition to distilled spirits and by the early 14th century allowed monasteries to house stills for making aqua vitae, or “water of life”. The infirmaries and herb gardens surrounding the monasteries provided medicines and formulae for special healing concoctions, the progenitors of modern liqueurs such as Benedictine and Chartreuse.

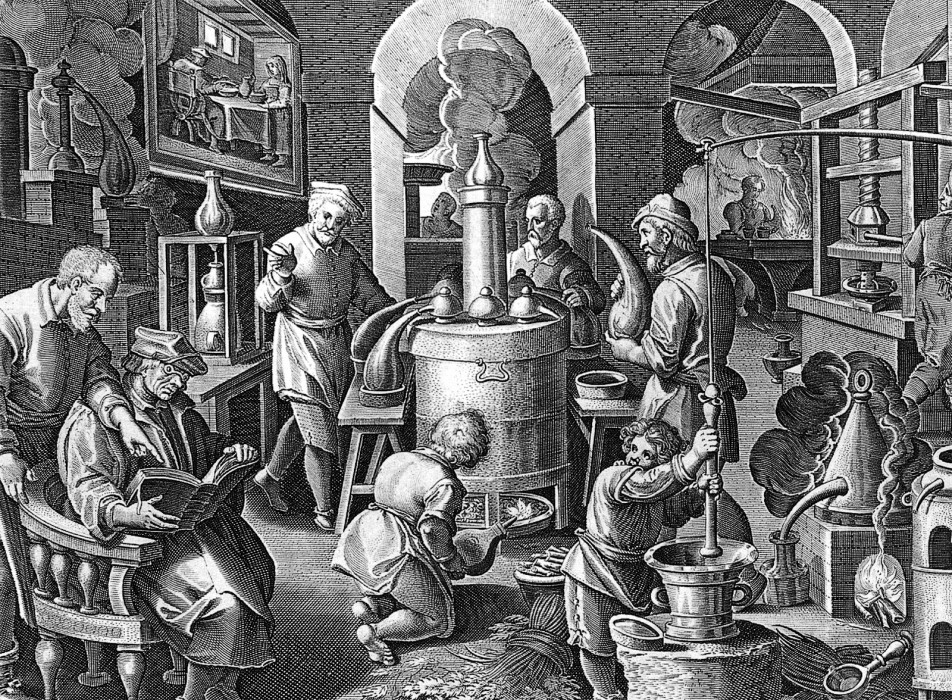

Distillers who supplied aqua vitae directly to the public were found in Italy as early as 1378, and royal houses began to employ distillers on their staff. By the fifteenth century, German authorities had become concerned about the ills of public spirits consumption, as people with no medical experience began to set up stills at home and sell their wares on holidays in front of their homes.

In 1494, the Scottish Exchecquer rolls cite the provision of eight bolls of malt to a friar for the making of aqua vitae; the use of cereals to distill spirits was already widespread in northern Europe. There was a distinction between simple aqua vitae, which was not redistilled over botanicals to prepare medicinal waters, as was often done in England and in the monasteries. The Gaelic translation of water of life, “uisquebaugh” was current among Gaelic speakers and was valued as a warming remedy in damp, cold climates.

The first printed book on producing distilled waters to treat a variety of ailments appeared in Germany in 1477. A spoonful of aqua vitae is recommended each morning to prevent illness, and if a little was given to a dying person, it was said he would speak before he died. Pictures in the book show a woman operating a still over a charcoal fire, surrounded by herbs, confirming the role of wise women who provided folk medicine to those too poor to see a physician. Around this time, distilled spirits also began to appear in cookbooks as a means of enhancing the presentation of foods, e.g., ignited spirits could be made to shoot from the mouth of a roasted peacock, sewn back into its skin and feathers.

Commercial distilling in industrial stills became common in the 17th century, and was frought with battles over licensing and taxation. Consumption of distilled spirits gradually lost its association with spiritual symbolism and medical treatment and instead became a public health issue, as abuse of spirits (often of dubious quality) became rampant. Nevertheless, reverence for fine spirits has endured as a testament to their ancient origins and mysterious powers.

Today, small craft distillers have begin to thrive in the U.S., presenting an alternative to the large commercial distilleries that consolidated their markets in the 19th and 20th centuries. The use of local ingredients and the resurrection of traditional techniques have distinguished microdistilleries, however quality remains dependent on the ability of the still, and the distiller, to produce a pure and enjoyable spirit. We are excited to be part of the craft distilling movement as well as the long tradition of bringing forth the “water of life.”